The $3.5 Trillion Question: How to Make Natural Resource Funds Work for Citizens

Just months after Kenya discovered commercial oil in 2012, the government called for the establishment of a natural resource fund (a kind of sovereign wealth fund) to save oil revenues for future generations. Yet Kenya is a country where over 60 percent of the population lives on less than $2 per day and only half of rural residents have access to clean water. Why would the government want to set aside oil revenues and invest them in U.S. and European markets when there are such desperate immediate needs in the country?

One explanation is that Kenyan leaders have heeded the lessons from other countries’ past experiences. As Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz said, “many countries with large natural resources have not done well. They’ve not done well in terms of growth, equity, poverty reduction, so much so that this is called the natural resource curse, and we’ve studied the causes and what can be done about it.”

When asked for recommendations for another emerging producer, Myanmar, Stiglitz reflected on successes in resource-rich countries like Norway and Chile. He then suggested that the Myanmar government put some petroleum revenues into a fund and invest them abroad for a time. Given volatile oil and gas prices, such a fund could stabilize wild swings in government revenue, improving the quality of domestic investments. Saving revenues abroad could also mitigate inflation or appreciation of the exchange rate associated with the influx of significant oil revenues. (Such appreciation would make it “difficult for farmers to sell their goods internationally as imports come in and destroy jobs in the country,” according to Stiglitz.) Additionally, a resource fund could protect and save these finite revenues for the benefit of future generations.

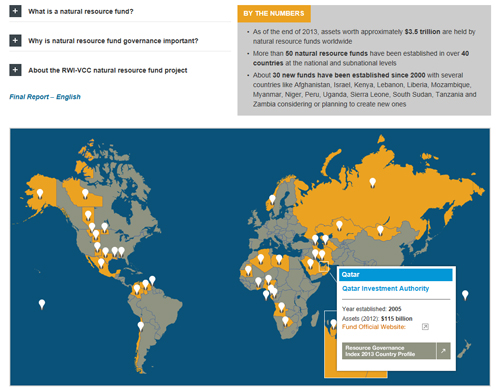

In countries as diverse as Canada, Lebanon and Uganda, and almost a dozen others, government officials are working on establishing new funds to manage their oil, gas and mineral revenues—in some cases years before any revenues start flowing. This trend seems set to continue, adding to the $3.5 trillion in assets already held by natural resource funds.

Yet, like national airlines or stock exchanges before them, it is possible that sovereign wealth funds have simply become a fashion among developing countries. If you are producing oil, gas or minerals, you simply must have one.

A potential problem is that such funds are not always benignly operated. It is true that authorities can use natural resource funds to improve the quality of public spending (by reducing spending volatility); create an endowment for the benefit of future generations; direct natural resource revenues to development projects like schools, hospital equipment, clean water and electricity (by allocating revenues to the budget for specific purposes); and protect oil, gas and mineral revenues from corruption and patronage.

However, in many cases they have been used as slush funds, serving as channels for nepotism and corruption. Natural resource funds have been used as sources of patronage by ruling families or parties in some countries, particularly (but not exclusively) those ruled by authoritarian regimes. A recent report by the Financial Times revealed that under the Gadhafi regime, the Libyan Investment Authority recorded over a billion dollars in losses from 2008 to 2010 through a combination of poor due diligence, excessive risk-taking, and patronage investments.

A just-released study from the Revenue Watch Institute – Natural Resource Charter (RWI-NRC) and the Vale Columbia Center (VCC) sheds light on natural resource fund activities. It shows that many funds are not meeting their policy objectives. In Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Trinidad and Tobago, for example, self-described budget stabilization funds have failed to mitigate expenditure volatility caused by swings in oil prices.

The indirect costs of poor fund management may be considerable. Managers of opaque funds can use them to reward political allies with jobs or investments in their companies; or they may accrue large losses in secret. Half of all natural resource funds are too opaque to study, despite the fact that they manage public money.

In some countries, like Angola, Iran, and Russia, governments spend money directly from their resource funds, circumventing budget processes and creating new channels for patronage. This undermines parliamentary accountability and public financial management systems, thereby harming institutional development. In short, a natural resource fund does not in and of itself improve natural resource governance—it can actually make things worse.

This is not to say that governments shouldn’t ever establish a fund. In the past decade, we have seen a proliferation of not just funds—about 30 new ones since 2000—but also transparency and good governance rules. In Ghana, Mongolia and Timor-Leste, for instance, governments have set clear objectives, enacted strong regulations, introduced independent oversight requirements, and required public disclosure of audits and extensive reporting.

The new report prescribes six steps for improving fund governance, drawing on the progress made by some of the countries whose funds we reviewed.

Kenya’s place on the spectrum of natural resource fund governance is as yet unknown. Less than two years after commercial discovery, the Kenyan government is “‘fine tuning’ a draft framework” for the fund, intended to shield the Kenyan economy from cyclical changes in commodity prices, build savings for future generations, and invest in infrastructure. Central bank chairman Mbui Wagacha summed up what’s at stake when he remarked that, “the resources that we own today also belong to our future generations.”

The full report can be found at our interactive website here.