African Oil and Gas Producers Will Face Taxing Challenges Post-Pandemic

Français »

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, experts predict Africa’s economy will shrink for the first time in over 25 years. For the continent’s oil- and gas-rich countries the impact of the pandemic coincided with and exacerbated a global drop in oil prices. A barrel of Brent crude oil fell from USD 60 in December 2019 to $20 in April 2020. One immediate consequence was a sharp fall in government revenues at precisely the time when governments needed to increase spending. Those countries most dependent on their oil and gas revenues have been hit hardest.

Implications for projects now in production

Nigeria, for example, relies on oil revenues for over 50 percent of its budget. The country’s 2020 budget assumed oil would average $57 a barrel. With the drop in price and demand the government lost 65 percent of its revenue in the first six months of 2020.

Ghana’s 2020 budget assumed an even higher benchmark price, at $62.60 per barrel. In July the country’s finance minister predicted oil revenue would be 50 percent lower than anticipated due to the pandemic.

Facing such economic challenges, governments are desperate to retain investment and jobs and to generate revenues. With the drop in oil prices, officials in some oil- and gas-producing countries will likely have to decide whether they will give tax breaks to oil and gas companies to attract or retain investment. The payments that oil and gas companies make to governments (in the form of production shares, taxes and royalties) are often larger per barrel of oil produced than the actual cost of production. When times are tight, this is where companies often look to cut their overall costs.

But tax breaks to oil and gas companies during price slumps have a checkered history. The wrong choice can mean countries lose out in the medium-to-long term, or companies gain a tax break that was unnecessary, reducing much-needed government revenue. Our NRGI colleagues have been examining the risk of a “race to the bottom” in how oil- and gas-producing countries manage tax issues in the pandemic context. In a new briefing, “A Race to the Bottom and Back to the Top: Taxing Oil and Gas During and After the Pandemic,” they consider a sample of 19 oil- and gas-producing countries, including six African producers, and draw out important insights for government officials as they consider options.

Companies’ operating costs and taxes in all of the studied countries are well below the current price per barrel. (See figure, below.) These costs matter because companies tend only to stop production when the market oil price is below the costs of continuing to operate the project: operating costs and taxes.

For instance, the average current per barrel operating cost in Angola is $9, with $15 in taxes (for a total cost per barrel of $24). There may be some higher-cost projects for which a tax break could ensure continued economic viability, but they are few. Similarly, although Ghana’s average operating cost is higher, at $16 per barrel, its tax on upstream production is only $5, and so the total costs for companies ($21) remain well below the current price per barrel. Nigeria’s average costs are $23 per barrel. The conclusion: tax breaks on most currently operating projects are likely unnecessary and a waste of public money.

Implications for projects on the verge of production

The research also examines oil and gas projects likely to be developed over the next five years. Companies may start to lobby governments to change these projects’ tax treatment, threatening to pull investment, and with it, prospective production, revenues and employment. But before governments act on such concerns, NRGI experts urge caution. Prices are unlikely to stay low, and might continue to cycle, even if long-term prospects are increasingly uncertain.

Tax policy has the most potential to attract oil and gas investors at the licensing stage; governments should focus on designing their tax regimes correctly at that stage. If officials are considering reducing taxes on projects awaiting development, they (and oversight actors) should ensure that the project would truly only become viable with a tax break and that the project would still provide sufficient value for the country. For most countries, relative to total oil and gas produced, the production from projects that could be delayed or cancelled is small.

If a government is considering a tax break then it should plan for uncertainty and use a progressive tax regime that will automatically respond to changing prices, or include a “sunset” clause. These approaches will help ensure that a government does not “lose the race back to the top” if prices rise.

Implications for new oil and gas producers

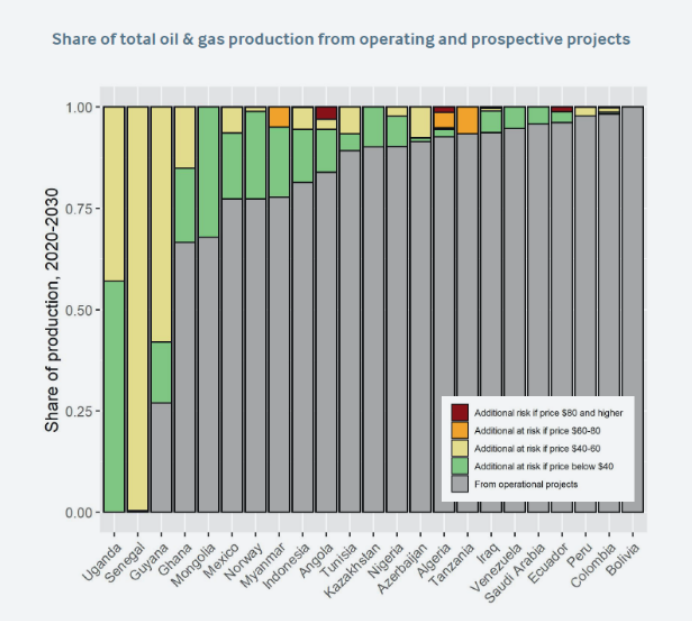

It is a different story for sub-Saharan Africa’s new producers, however. They will have to recalibrate their expectations. Uganda and Senegal may find their futures as oil producers cut short or disappointing. These two countries more than any others in the NRGI analysis have much of their future production in high-cost projects that companies might not develop. (See figure, below.) More than half of Uganda’s prospective oil production is at risk if prices dip below $40 again.

Even at prices between $40 and $60, well over one quarter of Uganda’s potential upcoming oil projects could be at risk. While there is never consensus on the future price of oil, the aggregate view of the world’s oil outlook suggests a gradual increase to just above $53 by 2025. In this scenario, investors may be less willing to invest their money in developing projects in Uganda.

In Senegal, the two projects (Sangomar and Grand Tortue Ahmeyim) that have secured a final investment decision appear to be going ahead, despite the pandemic. However, the potential for future proceeds is even more precarious than in Uganda; all of Senegal’s projected production over the coming decade is at risk even if the price per barrel hovers between $40 and $60.* Under the gradual climb to the $53 per barrel by 2025 scenario, the outlook for the development of future projects in Senegal is uncertain.

The immediate dilemma for oil and gas producers in the wake of the pandemic foreshadows a longer-term one: even if the price rises in a few years, the long term is less certain as major economies transition to using lower-carbon energy. Some studies estimate that if the world transitions quickly to clean energy (fast enough to keep global warming below 2°C), then the long-term price of oil land somewhere in the $40s. For new producers, particularly high-cost ones, the question is likely not one of tax breaks at all. The question is broader – how to recalibrate for a future where oil and gas play a much smaller role in the economy. Taking the long view is vital for Africa’s new oil and gas producers, now more than ever.

*One exception may be the Yakaar-Teranga project, which has an estimated break-even price of $32 per barrel for domestic gas (which will be its focus), though it has an estimated break-even price of $70 per barrel for gas for export. However, the project is facing other challenges related to the pandemic.

Silas Olan’g and Evelyne Tsagué are Africa co-directors at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Zeina Dowidar is a program associate at NRGI.