Might the U.K. and the U.S. Exhibit Leadership in Addressing State Capture and Legal (as well as Illegal) Corruption?

The leaked information in the Panama Papers from the law firm Mossack Fonseca have captured the headlines, placed Panama in the limelight, and provided an unprecedented glimpse into the world of hidden money and tax avoidance. Looking ahead, it is vital that we distinguish between legal corruption (such as that exposed by the Panama Papers) and illegal corruption (such as that exposed by the Unaoil scandal) and recognize that this is a moment for governments to take decisive action against both. Both the U.K.—with its Anti-Corruption Summit in May—and the U.S. have an unprecedented opportunity to make a difference.

Beyond Panama

The work of Mossack Fonseca may illustrate the web of options for hiding ill-gotten wealth, but the firm is just one of a vast and complex set of “enablers” of corruption and tax evasion around the world.

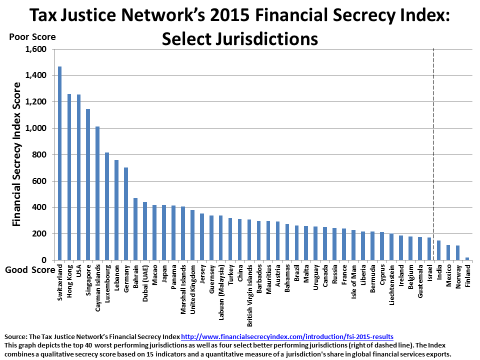

For those seeking secret shelters and corporate shells, the mighty United States (which unsurprisingly doesn’t feature much in the Panama Papers) is one of the world’s most appealing destinations: setting up a shell corporation in Delaware, for instance, requires less background information than obtaining a driver’s license. As seen in the chart below, this opacity, coupled with the size of the U.S. as a haven, means that it is being ranked the third-most secretive jurisdiction among close to 100 assessed by the Financial Secrecy Index. Panama ranks 13th.

Figure: Financial Secrecy Index

The U.K. has also been an important enabler: it has stood by as its offshore jurisdictions and protectorates operate as safe havens for illicit wealth, which the Panama Papers make clear. The British Virgin Islands, for example, were the favored location for thousands of shell companies set up by Mossack Fonseca.

Beyond tax shelters

The Panama Papers speak only indirectly to core aspects of today’s global corruption challenge, which is neither about Panama nor taxes. We ought to view the resulting scandals in a much broader light, and recognize the immense, complex webs of corruption that increasingly link economic and political elites around the globe. In particular, policymakers, the media and concerned citizens must seize upon the major pending challenges of tackling grand corruption, legal corruption, and persistent opacity—including among commodity traders—in preparation for the Anti-Corruption Summit.

Grand corruption

The most powerful figures who engage in high-level or “grand” corruption are hardly running scared following the Panama leak. These figures include kleptocrats as well as oligarchs who wield enormous influence on government affairs. Often, these players interact and collude with each other, forming high-powered public-private networks that make the traditional notion of corruption as an unethical transaction between two parties look like child’s play.

Corruption in these elite networks far transcends the unethical behavior of the typical tax avoiders, as it involves the abuse of power to accumulate power and assets, often via the direct plunder of public resources or large-scale bribery. The multibillion-dollar scandal embroiling the Brazilian oil giant Petrobras, which stretches across the country’s political and economic landscape and into many other countries as well, illustrates how grand corruption can inflict political and economic damage of historical proportions on a country.

The oil sector provides many more illustrations of grand corruption. Few company officials were likely more relieved by the Panama Papers scandal than those at Unaoil, whose own scandal had just erupted as the massive Panama leak came to light. Unaoil is an “enabler” company incorporated in Monaco that bribed and influenced government officials on behalf of multinational companies vying for lucrative procurement contracts. While overshadowed by the Panama leaks, the Unaoil case is more emblematic of the challenges in tackling global corruption: it shows the deeply ingrained practice of Iraqi government officials seeking bribes for the award of contracts and the willingness of companies to provide them. It also reveals the enabling role played by professional facilitators.

Corrupt elites, including those embroiled in the Unaoil scandal, often use structures like shell corporations and tax havens to hide their ill-gotten funds (along with real estate and other investments). However, even if the Panama Papers leak leads to reform of these financial structures, grand corruption will continue in many locations. It is noteworthy that the political fallout from the Panama Papers has been concentrated in relatively well-governed countries where accountability and anti-corruption systems are in place, as illustrated by the resignations of the prime minister of Iceland, the industry minister of Spain and the head of Chile’s Transparency International chapter.

In sharp contrast, President Vladimir Putin brushed off the leaked Russian information as a Western anti-Putin conspiracy; in China, discussion and dissemination were muffled via media censorship; and, in Azerbaijan, further details on President Aliyev’s family mining interests will hardly dent his hold on power. While the reforms that seem likely in the aftermath of Panama leaks will hopefully make it more difficult for tax dodgers and unethical corporations and individuals to hide dirty assets, these difficulties will not be hard to overcome for corrupt leaders who wield unaccountable power and enjoy impunity.

Legal corruption and state capture

The Panama Papers shed a sliver of light on the aspect of corruption that is perhaps most damaging and difficult to tackle: legal corruption and state capture (versus the illegal activities revealed by the Unaoil scandal). Around the world, powerful economic and political elites unduly influence the laws, policies and national and international institutions to suit their needs, fueled by the “money-in-politics” machine, which is protected by those same interests. Shaping the rules of the game for one’s own benefit, or the “privatization of public policy and lawmaking,” often by design a “legal” form of corruption, generates huge rents for the elite, increasing their power and a country’s political and economic inequality.

The kinds of resource-rich countries where we at NRGI work provide many illustrations. In Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Venezuela, for example, political elites have used state-owned resource companies to serve patronage agendas—often (though not exclusively) through legal means.

In many industrialized countries, an example of state capture is the tax system itself, parts of which are revealed by the Panama Papers. It is in the interest of elites to safeguard a worldwide network of secret offshore companies and tax havens where they can hide their wealth. But obviously this is done not only for tax avoidance purposes, but also because many have obtained their wealth in an unethical fashion, whether legally or not.

The evidence from the U.S. is telling: according to Zucman, since the 1950s the effective rate of corporate tax has decreased from 45 to 15 percent, whereas the nominal rate has only decreased from 50 to 35 percent. And U.S. companies make full use of foreign tax havens: according to a new Oxfam report, the top 50 American multinationals reported in 2008 that 43 percent of their foreign earnings came from five tax havens which accounted for only 4 percent of the companies’ foreign workforces. Further, Bourguignon reports that federal tax rates on the richest Americans fell by 15 percent between 1970 and 2004.

What should be done?

Upfront, we recognize that there are no easy solutions, especially because powerful decisionmakers benefit from this status quo. But there is the opportunity—and citizen pressure—to reform. Here we focus on selected paths forward, with a focus on transparency reforms and the kinds of commitments that governments should make ahead of the London summit.

First, take legal corruption and state capture seriously.

Transparency can be one game changer, especially if it addresses the channels of influence through which policy becomes “privatized.” Disclosures of campaign finance contributions, conflicts of interests, the assets held by (and tax returns filed by) politicians and public officials and parliamentary deliberations and votes can all help shift incentives away from abuse and reveal some of the networks at play.

Transparency will only help if citizens can actively scrutinize and engage with their governments, and make them accountable. Civic space is under attack in many jurisdictions, with activists and journalists facing intimidation, prosecution or worse. Securing rights of expression and assembly should be the business of any international actor concerned with anti-corruption or economic governance. For instance, as the World Bank and the IMF consider funding requests from governments like those of Angola and Azerbaijan—which have exceedingly weak records on protecting the environment of civil society—their officials should also prioritize not only transparency, but these civic accountability issues as well.

Furthermore, grand corruption will not reduce without more effective prosecutions and other sanctions that target bribe-takers, as well as the facilitators and middlemen of corruption, be they lawyers, accountants or fixers like Unaoil. Of course, law enforcement authorities should also remain vigilant against bribe-paying companies through mechanisms such as the more decisive enforcement of anti-bribery legislation as well as global law enforcement collaboration. But bribe-takers and facilitators have not faced sufficient scrutiny and sanction.

Second, get rid of shadowy corners.

Lessons yielded by recent events from the 2008 financial crisis to the Panama Papers suggest that major global players should not allow large corners of the global economy to escape scrutiny. The U.S. and the U.K. (with its offshores), should heed the calls for dismantling secrecy and tax havens. Seeds of effort, such as the U.S. government’s decision to require banks to know the identities of the individuals behind shell companies, are visible. But a step change is required, and the U.K. summit should be the venue where governments make concrete commitments.

Beneficial ownership transparency should become standard operating procedure, with governments following the example of the U.K., the Netherlands and others in setting up public registries, and joining the movement toward a global registry. In the case of resource-rich countries, establishing sector-specific registries may be the right place to start. This practice is now mandated by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Within the extractive sector, home country governments should subject commodity traders to payment disclosure requirements when doing business with governments and state-owned companies. Governments of countries like Switzerland, the U.K. and Singapore that are home to corporate actors shoulder significant responsibility here, especially in the current era of low commodity prices, when traders are entering into profitable new deals with cash-strapped resource-producing countries. Shining light in dark corners such as these will render them less susceptible to abuse.

Third, prioritize transparency and scrutiny when public resources are allocated.

Whenever a government allocates resources for exploitation, it ought to do so in a fully transparent fashion. The Open Contracting Partnership has made great strides in defining a gold standard for such reporting, including guidance on issues such as open data, corporate identifiers and beneficial ownership reporting.

NRGI research on oil and mining sector corruption shows that multiple types of high-value allocations require scrutiny. Attention often focuses on the allocation of exploration and production licenses. But the allocation of export, import or transport rights has led to corruption in countries including Indonesia, the Republic of Congo and Ukraine. And most of the oil sector cases prosecuted under the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act focus on another scenario: the award of service contracts, a precinct of the oil industry where the Unaoil and Petrobras scandals also took place. As this diversity of settings for resource-related corruption shows, transparency should be the default setting for any transactions that allocate public resources.

A major attack on impunity will be required for concrete impact, since transparency and freedom of expression are necessary, but insufficient. Governments including those of the U.S. and the U.K. should adopt reforms to address legal corruption and various forms of opacity—whether “dark corners” in Delaware, British Virgin Islands and the Kremlin, or oil traders headquartered in Geneva and London.

However challenging, an ambitious commitment to tackling corruption and impunity is not only needed, but demanded by societies, as events in Brazil and elsewhere show. This is a potentially “game-changing” global moment to make real progress.

Daniel Kaufmann is the president and CEO of the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Alexandra Gillies is director of governance programs at NRGI.

Authors

Daniel Kaufmann

President Emeritus