The Miracle That Became a Debacle: Iron Ore in Sierra Leone

Resource-rich, developing countries are experiencing deep turmoil due to low commodity prices. In many West African countries such as Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, the future of some large iron ore projects, under development for the last five years, is looking uncertain. These projects were conceived when iron ore prices were at historical heights, and officials and citizens alike foresaw transformational development outcomes. But now that the iron ore price has tumbled, these dreams may be dashed—or at the very least deferred.

The impact of the price fall on the plans of all of these countries is daunting, and their governments face steep challenges in reorienting national expectations. The case of Sierra Leone presents a particularly stark case. Three years ago, Sierra Leone’s media, using projections by the IMF and Sierra Leonean authorities, jubilantly predicted that the country would soon become Africa’s fastest growing economy. Unfortunately, this miracle—which was predicated on price projections that proved overly optimistic—did not take place. Worse yet, the erroneous forecast fueled expectations and prompted spending increases that weren’t sustainable.

The most dramatic impact, already being felt by Sierra Leoneans, has been the shutdown of operations at the country’s two largest mines, leaving 5,000 jobs hanging in the balance. The IMF now estimates a GDP contraction of 13 percent for 2015, and the national budget is under severe pressure. Other countries in the region are facing similar challenges, with lay-offs in Liberia and a delayed project start in Guinea.

The shutdowns come at a particularly bad time for the Sierra Leonean economy. The country is reeling from the Ebola crisis, and even before the most recent tumble in ore prices budget deficits stemming from reliance on overly rosy scenarios were widening.

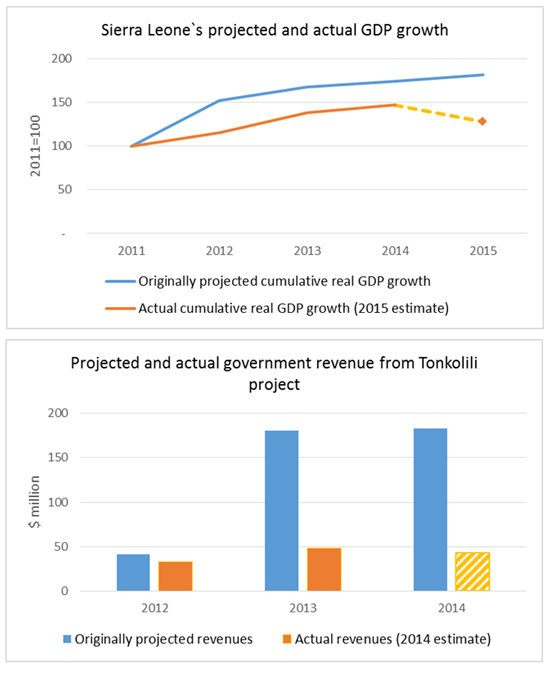

Using information from a November 2011 report, the IMF and government jointly projected that Sierra Leone’s GDP would grow by 51 percent in real terms in 2012 (which would have been a global record). The IMF warned about risks of slippage and called for cautious spending approach, but the projection was nevertheless incorporated into an IMF program to support Sierra Leone, read out in parliament, and disseminated widely. This optimism, also shared by other experts, was partly predicated on the fact that the post-conflict economy was stabilizing and macroeconomic management was improving, but mostly on the belief that the huge Tonkolili iron ore mine would start operations at the end of 2011, after a $2 billion investment. Government revenues from the project were forecast to reach $40 million in 2012 and $180 million in 2013, by which time the investor African Minerals would have offset most of its costs.

In the 2011-2013 period, these sunny projections prompted some to suggest that Sierra Leone would need a natural resource fund to channel the anticipated resource revenues towards development, and the government embarked on a pipeline of expensive projects and unbudgeted spending. Ambitious road and energy projects commenced, partly financed through loans, leading to an increase of 33 percent in external debt between 2011 and 2013. The government even secured a $315 million loan to build a brand new airport. Talk of the iron ore bonanza led to demands for more recurrent spending too, including increased public sector salaries as well as fuel subsidies. The private sector responded with an enthusiastic boom in construction.

As shown in figure below, the reality was that GDP did increase rapidly in 2012 and 2013 (15 percent and 20 percent annual growth, respectively), but it fell far short of the spectacular growth expected. Furthermore, some have questioned how much of this growth was actually captured by Sierra Leone’s government and citizens as opposed to foreign companies. In terms of tax revenues from the Tonkolili project, government receipts were less than $50 million annually, far short of projections. While corporate income tax on profits was foreseen from 2013 onwards, in actuality the mine never declared a profit before eventually stopping all operations in December 2014.

Original projections are from the IMF staff report. Actuals are from the latest IMF WEO database and the government of Sierra Leone.

There seem to have been three errors behind these overly optimistic projections:

- Assumption of high commodity prices. At the time of the major investments, iron ore prices were near their historical peak of $160/ton, but soon afterwards they started their descent to around $65/ton – the present-day price. In their calculations, both the IMF and the government assumed prices of $119/ton. Unpredictability is the norm in the extractive industries and makes projections difficult; modeling a more somber downside scenario and its implications would have helped the country limit its risks.

- Over-reliance on company projections of expansion. Because of limited access to “live” information on the projects, a lot of inputs for the government’s forecasting models were taken from company prospectuses, especially data regarding the time and cost of mining expansion. The primary investor in the country’s ore mines, African Minerals, was a new player in the industry, with no proven track record globally—a risky choice in a place like Sierra Leone, which is known to be a complicated environment. And there were further red flags: The chairman and founder of African Minerals, Frank Timis, had previously been found unsuitable to act as a director of companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, while the London Stock Exchange fined another company he founded £600,000 for the release of “overly optimistic” statements on an oil find. At Tonkolili, as time wore on, it became apparent that expansion was not proceeding according to plan. The company blamed project delays on a heavier-than-expected rainy season and cost overruns due to fuel misappropriation.

- Tax base erosion: Projections assumed perfect enforcement of tax obligations, but in reality companies have abused the tax loopholes and weak enforcement of laws in Sierra Leone. For example, African Minerals signed several discounted offtake agreements that ate into projected government revenues. It also entered into dubious transactions with a related party that not only decreased the tax bill but also reduced shareholder value, leading to the resignation of one of the company directors. No independent audit was conducted on behalf of the government.

Today, Sierra Leone's fight against the deadly Ebola virus is finally turning around, and there is growing hope for recovery. The IMF alongside other donors is providing additional financing to revive the economy. As part of the recovery process, the government is embarking on a review of its mineral policy. Part of such strategic thinking should probably include a stock-taking of resource wealth and projects both by government and civil society.

Other African countries that have been counting on large mining projects as key components of their growth strategies could apply the following lessons as they adjust their policies to the current reality:

- Projections of mining production should be conducted more openly and with a critical look at past mistakes, including due diligence on company figures, before being translated into policy.

- If both parties to mineral contracts decide to renegotiate contract terms to adjust to the downturn, officials should make sure the government can still increasingly benefit if commodity prices were to rebound again.

- Negotiating solid contracts is a key part of generating revenues from the mining sector, but ensuring compliance requires important additional efforts.

- Governments and civil society have a role to play in communicating honestly the challenges to citizens so that expectations reflect the new and difficult reality.

David Mihalyi is an economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute. He was an ODI fellow in the Ministry of Finance of Sierra Leone between 2011 and 2013, working as an economist in the budget bureau.