Rio Tinto, Mongolia, and the Art of Negotiating Amidst Price Volatility

Negotiating complex mining deals can be challenging for resource-dependent countries under any circumstances. But commodity price volatility adds an additional challenge to the mix, as Mongolia's recently concluded renegotiation with Rio Tinto on the Oyu Tolgoi project illustrates.

From dispute to agreement

Few natural resource projects are as significant as the Oyu Tolgoi copper mine, the biggest ever foreign-investment project in Mongolia. But the project has hit myriad snags since the signature of the deal between the government and Rio Tinto in 2009. Faced with cost overruns estimated at around $2 billion and the realization that the state's much-heralded 34 percent equity ownership would likely not pay dividends for decades, the government became keen to revisit the terms a few years into the project.

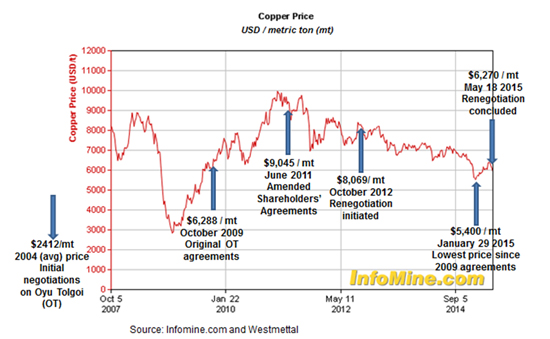

Discussions around Phase II, a multibillion-dollar underground expansion, provided the opportunity, and the government sought renegotiation with Rio Tinto in October 2012. Prospective lenders like the IFC and the EBRD required government sign-off on the Phase II financing plan; this provided the government with negotiating leverage to revisit problematic aspects of the earlier phase, including cost overruns, tax liability and Rio Tinto's management services fee. At that time, Mongolia was likely emboldened by relatively high copper prices (see chart below) and its status as the "world's fastest growing economy." The government had also successfully negotiated an earlier amendment in June 2011 (near copper's peak price) resulting in limited but positive changes for Mongolia.

Anatomy of a deal

Finally in May 2015, after more than two years of strained on-and-off negotiations, Rio Tinto and Mongolia reached an agreement. As with the initial Oyu Tolgoi contracts, and in line with international good practice, the new agreement is publicly available. Taken in combination with company and government statements, this makes it possible for observers to start analyzing the deal. As the table below indicates, each side can claim certain victories.

|

Key terms of May 2015 Oyu Tolgoi agreement: Victories for each side |

|

|

Rio Tinto

|

Government of Mongolia

|

Rio Tinto estimates that the agreement results in a value transfer to Mongolia of around $148 million, or 2 percent of the overall value of the project. Industry analysts have called this as a small price to pay for such a significant project, with one saying that the deal was basically "adjusting the terms back to what they should be on any mining project in the world," and another that "there are no momentous changes." This gives the impression that the agreement's main elements could have been agreed much earlier.

So what took so long, and why did they finally agree?

The length of the Oyu Tolgoi negotiations and the timing of the agreement are related at least in part to shifts in bargaining power. These shifts are common during the life of a natural resource deal. In this case commodity price changes and corresponding economic and political pressures played a particularly important role. In theory cyclical price changes should not significantly influence decisions for long-term projects like Oyu Tolgoi. But in practice resource companies do make decisions with an eye on prices and try to take advantage of price dynamics in negotiations.

In the Oyu Tolgoi case, copper's downward price trend for much of the renegotiation period (a 33 percent drop from October 2012 to January 2015), progressively weakened the government's hand. This fall allowed Rio Tinto to argue against fiscal changes and to create the impression that it could live without fast-track development of Phase II.

As prices faltered and softening Chinese demand left Mongolia's economy in a serious slump, the Mongolian government lost even more leverage. The dispute with Rio had direct and reputational impacts, and foreign direct investment plunged from $4.45 billion in 2012 to just $0.51 billion in 2014. Mongolia's mining investment attractiveness ranking dropped from the 38th to the 69th percentile.

Eventually the economic pressure produced a political shift. By late 2014 the new prime minister Chimediin Saikhanbileg was focused on a quick resolution to the impasse with Rio Tinto and secured backing for his approach through a text message referendum.

While prices and politics softened the government position, the eventual deal was not totally one-sided. So what brought a previously intransigent Rio across the finish line? Price dynamics may have had a role, this time in the form of an uptick of 17 percent in copper prices in the months preceding the agreement Rio Tinto's stated optimism on the future prospects of copper and interest in timing Oyu Tolgoi's next phase to come online as the copper market recovers may, as suggested in the Financial Times, have accelerated previously stalled negotiations.

Lessons learned

Oyu Tolgoi's key lesson for countries in similar situations is that any natural resource deal renegotiation must be thought through strategically and with eyes on both the commodity price cycle and political economy impacts. When circumstances such as price are in the government's favor, it is important for officials to act quickly to achieve the best possible deal while recognizing the limits of negotiating leverage. Waiting or overestimating the government's bargaining position runs the risk that volatile factors such as commodity prices may change in an unfavorable direction. Such changes not only create direct shifts in bargaining power, they can also result in secondary impacts (e.g., macroeconomic deterioration or reputational risks from prolonged renegotiations) that further weaken the government's hand.

Finally, the difficulties of deal renegotiation underscore the importance of ensuring that initial agreements (such as those currently under consideration for Mongolia's other mega-project, Tavan Tolgoi) are strongly negotiated in the first place. This should include provisions (such as fiscal terms) that are sufficiently flexible to adapt to changing circumstances so as to avoid renegotiations where possible. But governments and companies must also recognize that renegotiations do happen. This can potentially be anticipated by including periodic review mechanisms in contracts. Another essential element is investing in government negotiating capacity (e.g., having an established negotiating team, bringing in outside support – if necessary – early in the process, adopting a strong communications strategy, etc.) so as to ensure that when price levels and political factors require it, both sides are well placed to efficiently negotiate adjustments to the initial agreement.

Amir Shafaie is a senior legal analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute.

Authors

Amir Shafaie

Legal and Economic Programs Director