What Makes an Accountable State-Owned Enterprise?

This commentary was originally posted on the Brookings Institution’s Future Development blog on 26 March.

It is no accident that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have been at the center of many of the world’s biggest corruption scandals—from Brazil’s “car wash” money laundering scandal involving Petrobras to devastating mining deals in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These companies sit at the intersection of complex, billion-dollar commercial activities and the dealmaking and rent allocation powers of the state and political elites. Their missions often include a broad mix of contradictory goals. And they too frequently operate opaquely, subject to political manipulation and free from strong oversight.

Our work in the oil and mineral sectors has acquainted us with the heavy costs of unaccountable SOEs. In countries with large extractive sectors, SOEs play an oversized role in the fiscal health of the state. Corruption or inefficiencies among such enterprises send damaging shocks across the economy and political system. Yet, the extractive industries also provide examples of strong, modern SOEs that have been drivers of successful natural resource management, such as Colombia’s Ecopetrol and Norway’s Statoil.

Comparing the success stories and the challenging cases side-by-side does not produce easy answers for how to achieve accountability. The case of Brazil’s Petrobras illustrates the difficulty of charting a simple road map. For years, the company was celebrated for its corporate governance systems and attracted massive foreign investment; meanwhile, it helped political elites siphon off billions of dollars in public funds, fomenting a national political crisis.

As the Natural Resource Governance Institute prepares to join discussions about SOE integrity at the OECD’s March 27-28 Global Anti-Corruption and Integrity Forum, which will build on the OECD’s groundbreaking Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises, we want to share a few ideas regarding what makes an accountable SOE.

Reporting practices and checks and balances matter, and they can be measured

Though insufficient to prevent corruption on their own, strong corporate governance and thorough public reporting are the starting point of SOE accountability. The OECD guidelines provide a rigorous set of goals in this regard, as do standards set by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

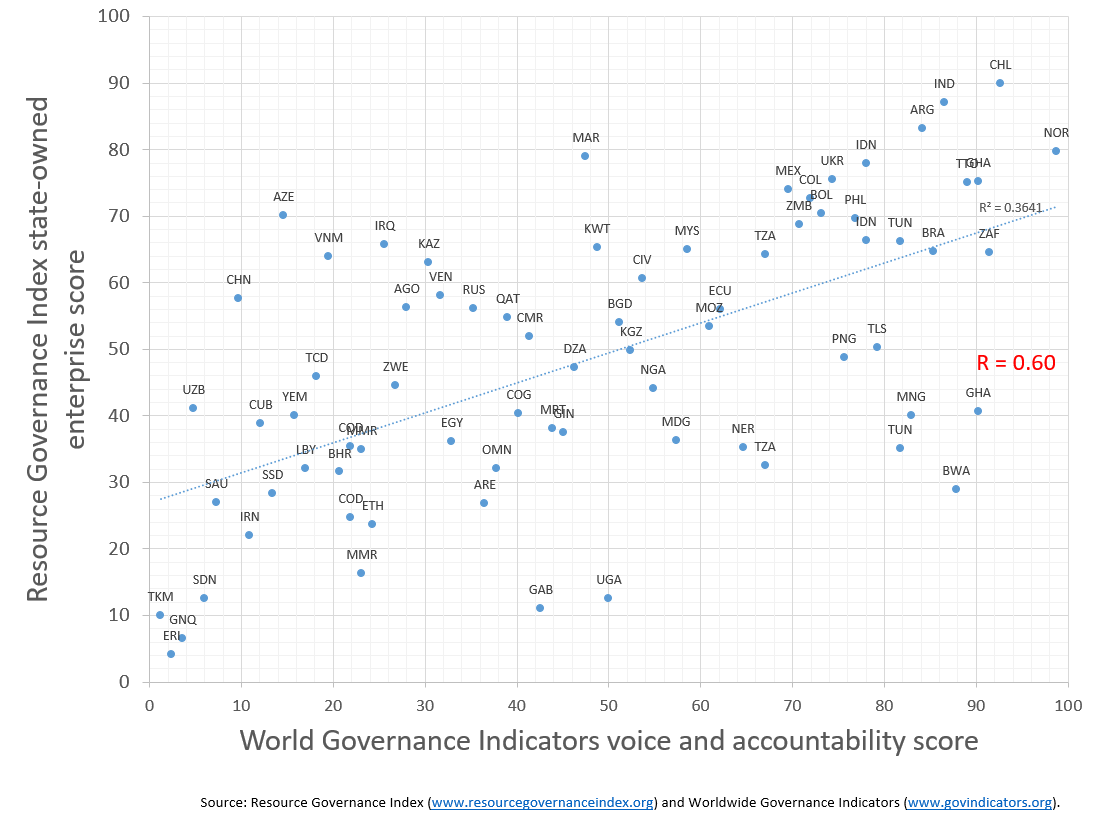

The 2017 Resource Governance Index assessed the performance of 74 SOEs across 10 governance and transparency practices. The practices assessed by the index, which focuses more on accountability than managerial efficiency, include the companies’ public reporting practices, audit provisions, and conflict of interest protections. As shown in Figure 1, the need for improvement in SOE governance is enormous, with only nine companies receiving a “good” score and many influential SOEs failing. To help spur improvements, we have created a Guide to Extractive Sector State-Owned Enterprise Disclosures that draws on the examples of well-governed SOEs and serves as a jumping-off point for developing better company-specific reporting regimes.

Figure 1. Performance of state-owned oil and mining companies in 2017

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: Resource Governance Index (RGI)

In addition to formal transparency and corporate governance practices, fully assessing the results that SOEs deliver to citizens requires a broader approach. Our experiences point to several additional factors to consider alongside those practices measured by the index.

Performance benchmarking is critical

SOEs often manage huge budgets and control valuable national assets. When accountability is lacking, they tend to deliver a poor financial return on these investments. Analyzing SOE performance is complicated by the multiple missions that SOEs often pursue, which is why there can be no one-size-fits all approach. But a good starting point is assessing whether the SOE has achieved the goals laid out by the government and the company’s own leadership. These goals must be concrete and time bound. International benchmarks can also help. Public officials and analysts can compare the performance of their SOEs against private companies to assess whether the country is receiving good value for money from its enterprises. (The Natural Resource Governance Institute will also soon launch a new dataset covering over 50 national oil companies, providing information on revenue generation, taxation, and financial and operational performance.)

Control of SOE corruption requires a mix of political, enforcement, and institutional responses

Law enforcement, whistleblowers, journalists, and activists have revealed possible instances of corruption in many SOEs. SOE officials have recently been accused of receiving bribes in Algeria, Brazil, Colombia, Iraq, and Venezuela; awarding contracts to politically favored companies in Russia, Nigeria, and the DRC; and channeling money in illicit directions, such as funding militia groups in South Sudan. Clearly, cases like these and others provide useful indicators of subpar SOE accountability. However, the fact that we know about these cases often points to positive dynamics in the country, such as active enforcement of anticorruption laws or the presence of effective watchdog groups, which are assets not present in all jurisdictions. Indeed, both effective law enforcement and external oversight are key pillars in controlling SOE corruption, along with strong internal safeguards (such as due diligence and procurement systems) and leadership from the company’s political bosses.

Empowered oversight delivers accountability gains

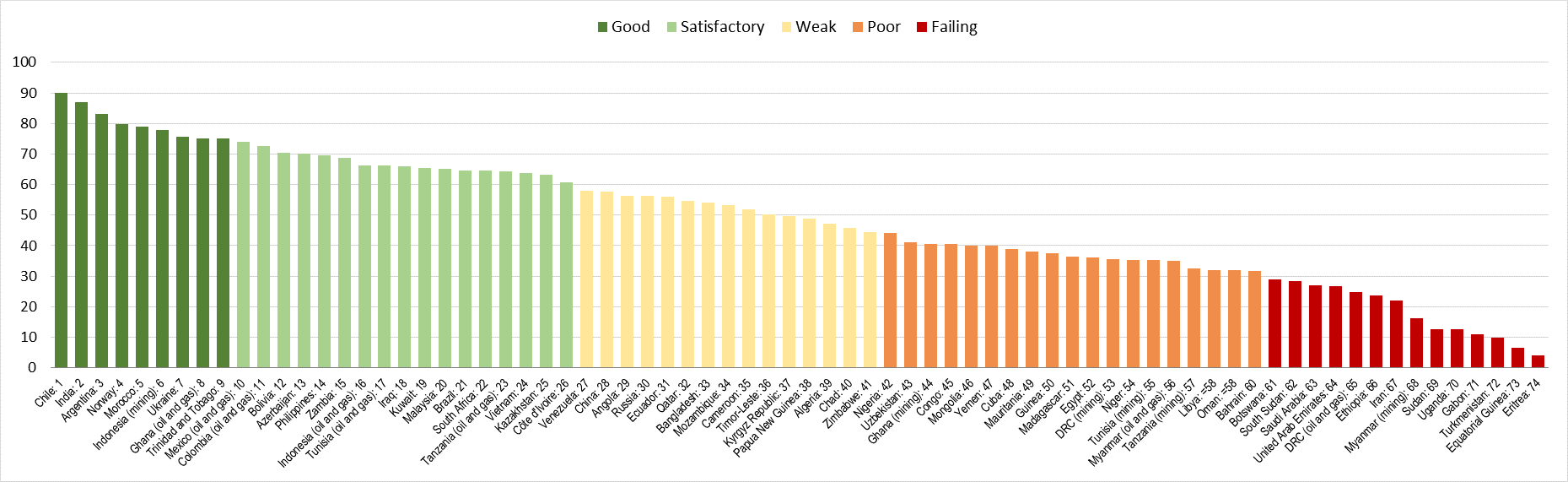

To ensure that companies are held to high performance and ethical standards, those actors charged with watching over them—often ministries, tax authorities, auditors-general, parliament, and civil society—must have the political space, financial means, and knowledge necessary to scrutinize, pose tough questions, and demand results. In Mexico, for instance, a coalition including the sector regulator and leading NGOs is developing a shared approach to public monitoring of the country’s new petroleum contracts, including those assigned to Pemex. There is strong evidence that voice and accountability matters for corruption control at the country level. Further, the data point to a strong association between a country’s overall levels of voice and accountability and the standards of governance of that country’s SOEs in extractives, as shown in the Figure 2. Assessing the presence of active and effective oversight is, therefore, another approach to gauging SOE accountability.

Figure 2. Resource Governance Index state-owned enterprise score versus World Governance Indicators voice and accountability score

Effective reform will stem from honest self-reflection and context-specific approaches

Extractive sector SOEs vary tremendously, from efficient companies always seeking cutting-edge governance innovations to corrupt shells with few operational capabilities. Most SOEs lie somewhere in-between, with a mix of skills and struggles. To create a tailored and realistic reform agenda, a rigorous and forthright analysis of the company’s strengths and shortcomings—within the company and by its state owners—is critical. Many reform efforts have focused on marginal, formal steps when, in reality, only a radical revamp would reverse the legacies of politicization and dysfunction that have grown over time. International actors, governments, and SOEs alike have often failed to acknowledge the true scale of the accountability challenges at hand. Assessing the different aspects of accountability mentioned above, along with a context-sensitive diagnosis of the SOE and the country’s broader political economy context, and preparedness to consider bold reform options, will increase the chances of achieving real gains.

Daniel Kaufmann is the president and CEO of the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Alexandra Gillies and Patrick Heller are advisors with NRGI.