The DRC-Zambia Battery Plant: Key Considerations for Governments in 2024

-

The partnership between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia to develop battery precursors is central to Africa’s ambitions to add more value to its minerals. However, public information about the project is limited.

-

Based on available information, the location of the precursor plant remains a source of disagreement. Regional bodies have a key role in developing mechanisms to ensure an equitable share of benefits irrespective of which country hosts the plant.

-

The Congolese and Zambian governments should consider the challenges in attempting to source the required minerals from the two countries alone, and explore wider regional coordination to meet the need for nickel and manganese.

-

The role of other global actors, such as the U.S., EU and China, remains unclear, but how the DRC and Zambia navigate the geopolitical complexities will be critical for the project’s success.

-

Greater transparency and stakeholder consultation will help the governments make the difficult decisions necessary for the project to go ahead and increase the likelihood of it benefiting the Congolese and Zambian peoples.

African countries are gearing up to play a pivotal role in the production of clean energy technologies for the global energy transition, and not just as suppliers of raw minerals. They seek to maximize their role in regional and global value chains by adding value to the resources extracted from their soil.

One key initiative is the partnership between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zambia to produce nickel, manganese and cobalt (NMC) battery precursors. A precursor is an intermediate input to a complete battery, which the two countries aim to ultimately also produce. However, without a large regional market for the electric vehicles that use these batteries, production of complete batteries will be challenging. For now, the focus is on producing and exporting precursors that foreign battery manufacturers will use.

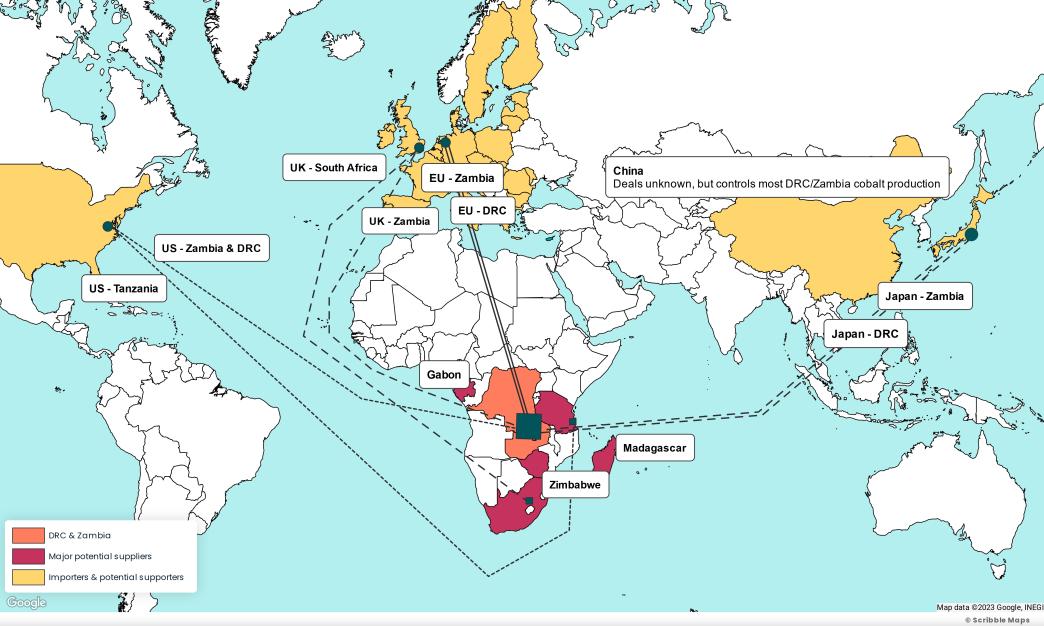

Planning for the precursor plant got properly underway in 2023, though details have been scarce. The status of a long-awaited pre-feasibility study is uncertain. There are conflicting statements about whether it has been completed and if it will be made public. The two countries have not disclosed their cooperation agreement or subsequent framework agreement. Various memoranda of understanding (MOUs) between these two countries and the United States and European Union are in the public domain, but further details remain behind closed doors, at least until roadmaps (action plans referenced in the EU MOUs) are developed next year. Little is known about other agreements that could impact the mineral sector and therefore the project—such as those between the DRC and Japan; Zambia and Japan; and Zambia and the United Kingdom. China’s dominance of cobalt production in the DRC and Zambia, including through state-owned companies, means it could have a significant influence on the precursor plant, but its role is uncertain.

Congolese and Zambian civil society actors are concerned about the lack of information and limited stakeholder consultation. In November 2023 they established the Pamoja Critical Minerals Forum to monitor and engage the governments on these plans and ensure that the plans reflect community voices.

Based on available information, we see four issues around the precursor initiative that the two governments should consider in 2024:

- Precursor plant location

- Mineral sourcing

- Role of international deals

- Transparency and multistakeholder engagement

Precursor plant location

Stakeholders suggest that this remains a point of disagreement between the DRC and Zambia. The governments initially agreed to construct the precursor plant in a cross-border special economic zone, but it seems that this shared site may be ultimately deemed unviable. The zone will therefore likely sit in one country or the other, and both countries aim to be the host. They have provisionally respectively earmarked the special economic zones of Kinsevere in DRC and Sub-Sahara Gemstone Exchange Industrial Park in Zambia.

Starting the project will be challenging regardless of its location. The independent prefeasibility study will likely recommend a location for the plant to maximize its economic viability and minimize environmental and social harms. To bolster the project’s prospects, the governments should accept the study’s recommendation in the absence of any major concerns. While it will not be easy for either country to agree to having the plant in the other, they can explore mechanisms to ensure an equitable share of benefits with the help of the regional bodies already active in the project such as the African Union’s African Minerals Development Centre, the African Development Bank, the UN Economic Commission for Africa and Afreximbank. For example, the country that does not host the plant could get a share of government revenues that the plant generates and have certain opportunities reserved for its workers, goods and services. This is a critical test for regional coordination: the proof of concept that the African Green Minerals Strategy calls for to catalyze other and wider coordination efforts.

Mineral sourcing

Stakeholders suggest that the governments aim to source all the required nickel, manganese and cobalt only from the two countries. The capacity of the plant and specific precursor design (including the ratio of nickel, manganese and cobalt) that the governments target will partly determine the feasibility of this approach. These parameters will be clearer after completion of the prefeasibility study. The plant that was initially envisaged would be large by global standards, producing around 100,000 tonnes (t) of NMC (622) precursors (one of the most common types currently demanded) a year. This would require around 48,000 t of nickel, 15,000 t of manganese and 16,000 t of cobalt that has been refined into sulfate.

The DRC and Zambia will find it challenging to source a sufficient amount of ores of the three metals and refine them into sulfates without involving other countries in the region. Neither the DRC nor Zambia currently refines any cobalt production into sulfate, but prospects are promising. Plans for a cobalt sulfate plant are advancing in Zambia, and World Bank analysis suggests a plant could also be viable in the DRC.

Production of nickel and manganese sulfate is less certain, however. Zambia produced around 4,000 t of nickel in 2022. First Quantum’s large nickel mine, Enterprise, started production in Zambia this year, which will add a massive 30,000 t a year on average. Nevertheless, this volume may still be insufficient for Zambia to meet the precursor plant’s needs on its own even if refining facilities were constructed and all production was supplied to the plant. Nickel exploration in the DRC is underway. Given only 19 percent of the country has been properly explored, this exploration may yield discoveries. However, with nickel mines taking an average 17.5 years from discovery to production, supplying the precursor plant is a far-off prospect.

Time is also a factor for manganese. Manganese is mined in the DRC and Zambia, currently by artisanal and small-scale operators. Formalizing these operations, including to reassure potential buyers of the precursors that the supply chain meets high ESG standards, and going on to build refining capabilities will be challenging.

The two countries could potentially meet these challenges over time, but there is no time to waste. The rapid evolution of battery technologies and global scramble for minerals mean that the longer this project takes to come to fruition, the harder it will be to attract investors and secure minerals for the precursor plant from the DRC, Zambia or elsewhere that haven’t already been tied up in long-term offtake agreements. The two governments should therefore utilize the African Continental Free Trade Agreement and start engaging other African countries on potential supply. Gabon and Madagascar have been cited as potential suppliers of battery grade manganese and nickel, respectively. Other countries, such as Tanzania, Zimbabwe and South Africa, are also possibilities. However some of these countries, such as South Africa, may actually harbor their own battery ambitions: further highlighting the importance of regional coordination to determine an approach from which all countries benefit.

Role of international deals

There is little information in the public domain on the specific support that the U.S. and EU intend to provide to the DRC and Zambia’s precursor ambitions. G7 support for the Lobito Corridor railway appears to have the most momentum currently. This project could increase investment prospects for value addition in DRC and Zambia by improving the route to market, but the railway could also be used to export unprocessed minerals. The implications for the precursor plant are therefore currently unclear.

It remains to be seen whether U.S. and EU will “put their money where their mouth is” in terms of specific support to the plant, and what the DRC and Zambia commit to in exchange. While the precursor plant could become a focal project of the U.S.-led Mineral Security Partnership or an EU strategic project under the bloc’s Critical Raw Materials Act, none of the parties have given such an indication.

Private investment and financing for the project will also depend on whether the U.S. enables buyers of mineral products processed in the DRC or Zambia to benefit from incentives offered by U.S. legislation. Only minerals processed in the U.S. or a country with which it has a free trade agreement qualify for the Inflation Reduction Act’s electric vehicle tax credits, for example. As the Carnegie Endowment’s Zainab Usman has highlighted, adjustments to the African Growth and Opportunity Act or other legislative instruments are needed for the DRC and Zambia (and other African countries) to qualify. Eligibility for U.S. incentives would increase the likely demand for DRC-Zambian precursors, and as a result, the attractiveness of the project to investors.

In the meantime, Chinese authorities and companies are not standing still amid all the talk and action from G7 countries. How the DRC and Zambia leverage this geopolitical competition while navigating the resulting complexities will be critical. It remains to be seen how these various actors will manage Chinese dominance of cobalt production when establishing supply for the precursor plant. Morocco’s experience may generate lessons as it seeks to utilize Chinese investment in battery manufacturing and its U.S. free trade agreement to export batteries to the U.S. and Europe.

Agreements between the likes of the U.S. and EU and other African mining countries could also impact the prospects of the precursor plant. For example, the U.S. is supporting the construction of nickel refining facilities in Tanzania but the deal stipulates that the battery-grade nickel will be exported to the U.S. Gabon, currently an exporter of manganese ore, could need similar support to start refining. While Gabon would benefit from the commencement of refined nickel exports irrespective of their destination, a deal that prevents exports to other parts of Africa could inadvertently stymie regional integration and the more transformative impacts that it would bring. Significant coordination is therefore required between both African governments and other governments.

International deals that could affect the DRC-Zambia precursor plans

Transparency and multistakeholder engagement

The Pamoja joint statement calls for greater transparency around plans and deals related to the precursor project and transition minerals more generally. Initially, this applies to disclosure of the prefeasibility study once completed and any inter-state deals not yet in the public domain. Going forward, the Congolese and Zambian governments should disclose subsequent agreements such as the EU roadmaps as well as any between the governments and investors in mining and value addition projects. The governments should also increase consultation with other stakeholders, including civil society actors.

The stakes are high for the DRC and Zambia with these projects. More transparency will help catch mistakes and ensure that the projects generate the intended benefits for the Congolese and Zambian peoples. Greater public awareness of the various opportunities and trade-offs should provide the governments with space to make difficult decisions—for example, the location of the precursor plant and sourcing of minerals. Building more public consensus and trust will also support the credibility of long-term planning and stability of the regulatory framework, and therefore increase the ability of the DRC and Zambia to attract investment.

People in the DRC and Zambia could benefit greatly from precursor production in their countries, particularly if the associated energy and transport infrastructure is leveraged for wider use. However, government efforts in other policy areas will be at least as important. For example, as Zambia aims to significantly increase copper production, the government should ensure it manages the upstream effectively. Other value addition opportunities, such as scaling up copper manufacturing in DRC, also hold at least as much, if not more, promise. Given that the complexities of the precursor project risk absorbing large amounts of the governments’ time, money and political capital, officials must weigh the opportunity costs carefully.

Authors

Silas Olan'g

Africa Energy Transition Advisor

Thomas Scurfield

Africa Senior Economic Analyst