New Tool Helps Analyze IMF Forecasts Across Resource-Rich Countries

“It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” So goes one widely cited and misattributed maxim. Given the complexities of social and economic phenomena, making accurate predictions about how different countries will fare is an almost hopeless task.

Nevertheless, economists await the biannual release of the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook (WEO), which provides detailed five-year forecasts for a wide array of economic variables for every country, with great interest.

Though none expect the forecasts to be spot-on accurate, economists rely on them in their work as an impartial and sophisticated projection of economic trends—assuming no major policy change or shocks in the years ahead. Governments, private sector players and citizens alike can therefore use them as a baseline for planning.

We at NRGI have been reviewing projections attentively, as economic volatility is a key concern across the resource-rich countries where we work. Future resource revenues are inherently uncertain, which makes government planning difficult. As a result, we sometimes see authorities overspend on poorly planned projects in boom times and harshly cut spending when prices or production fall. Volatility of exchange rates, inflation, and government spending can cause businesses and households to spend in a manner than exacerbates the challenges.

In order to assess how countries have been coping with resource sector volatility and uncertainty, it is useful to look back at previous projections and compare that with the actual outcome. This is why we have built the World Economic Outlook Forecast Tracker. It allows users to plot how IMF WEO projections evolved over the years for a handful of variables and compare them with actual outcomes. Here we discuss three possible applications for the tool.

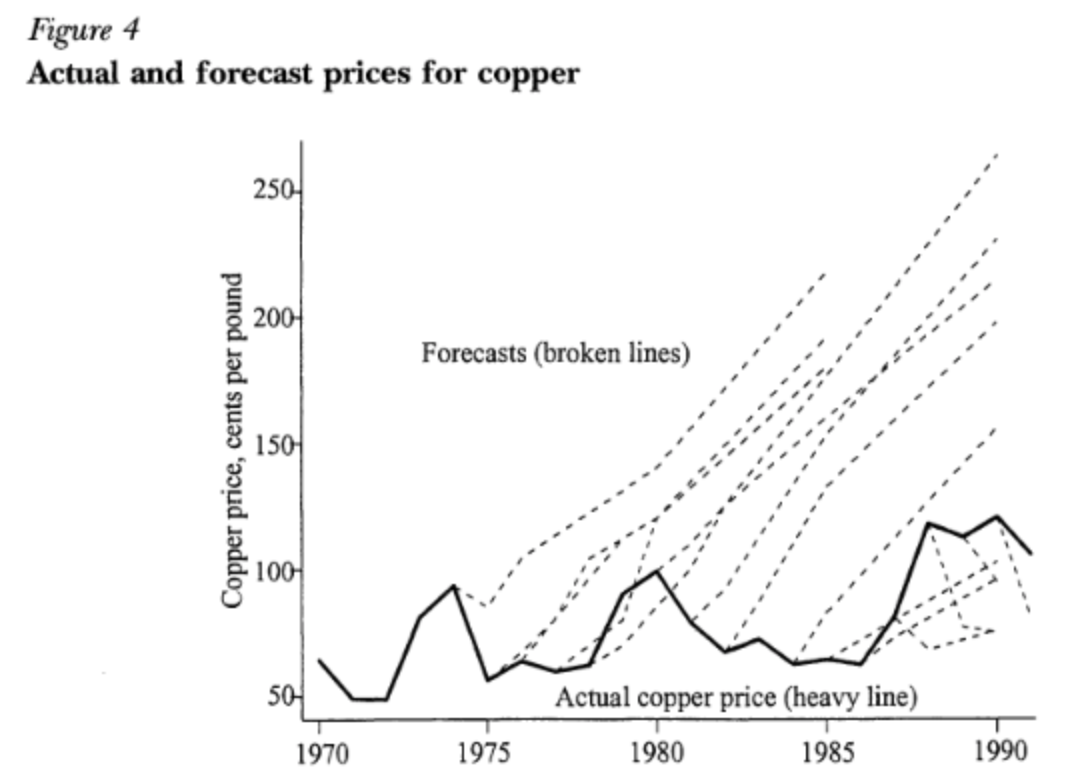

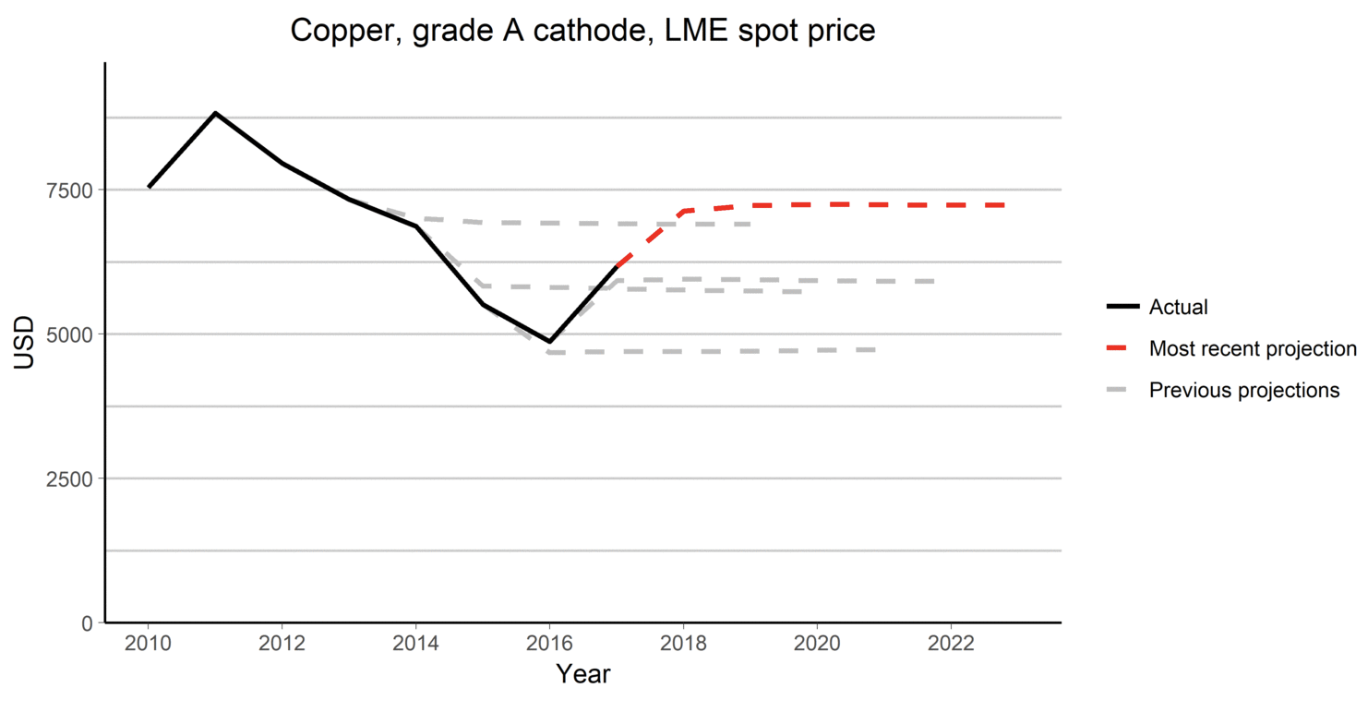

In one use case, we explore how commodity price projections have evolved over time. Nobel laureate Angus Deaton pointed out how optimistic the copper price forecasts used by the World Bank were in the 1970s and 1980s. Using our tool allows to contrast these over-optimistic forecasts with the IMF’s recent copper price forecasts. These show that IMF commodity price projections now assume that beyond some short-term corrections (based on commodity future markets), prices will generally flatten out (driven by inflation and demand). This forecasting approach makes sense; as research suggests, any forecast of oil prices beyond six months into the future is no more helpful than using the price today.

Historic copper price projections

Source: Angus Deaton, “Commodity Prices and Growth in Africa,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 13, no. 3 (Summer 1999): 23-40

Latest copper price projections:

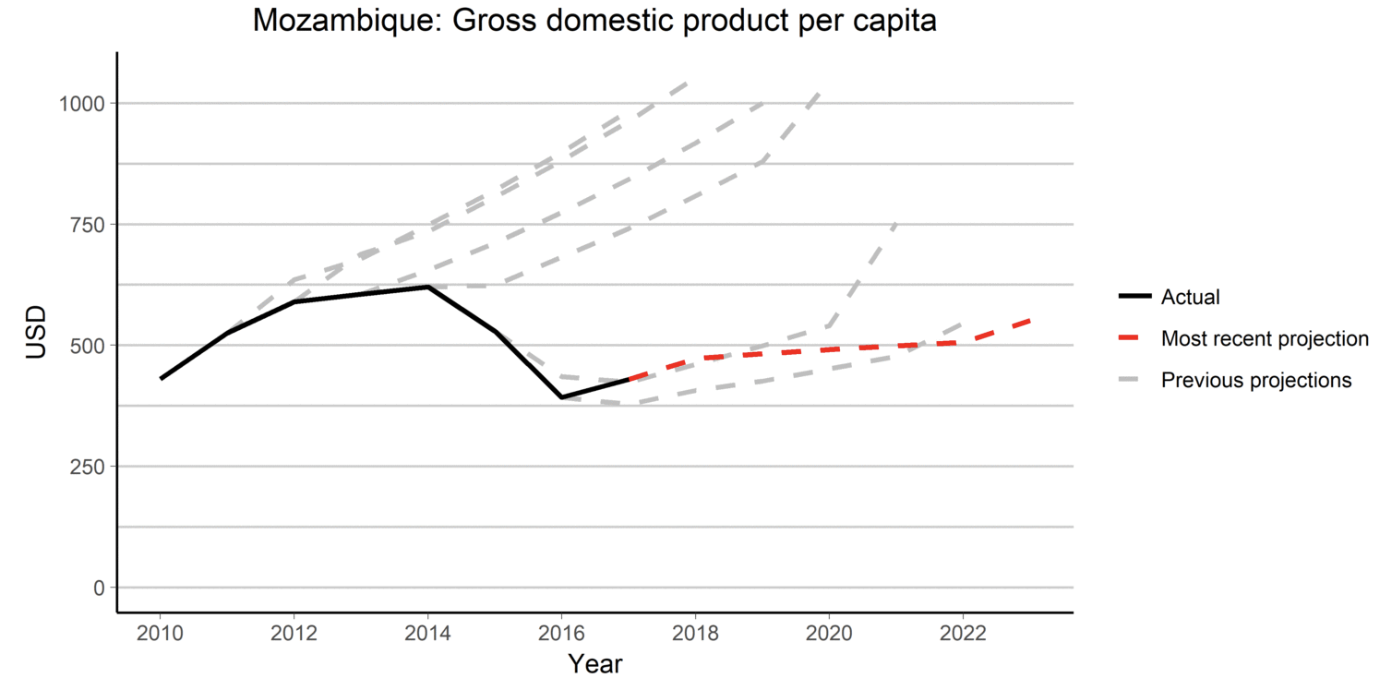

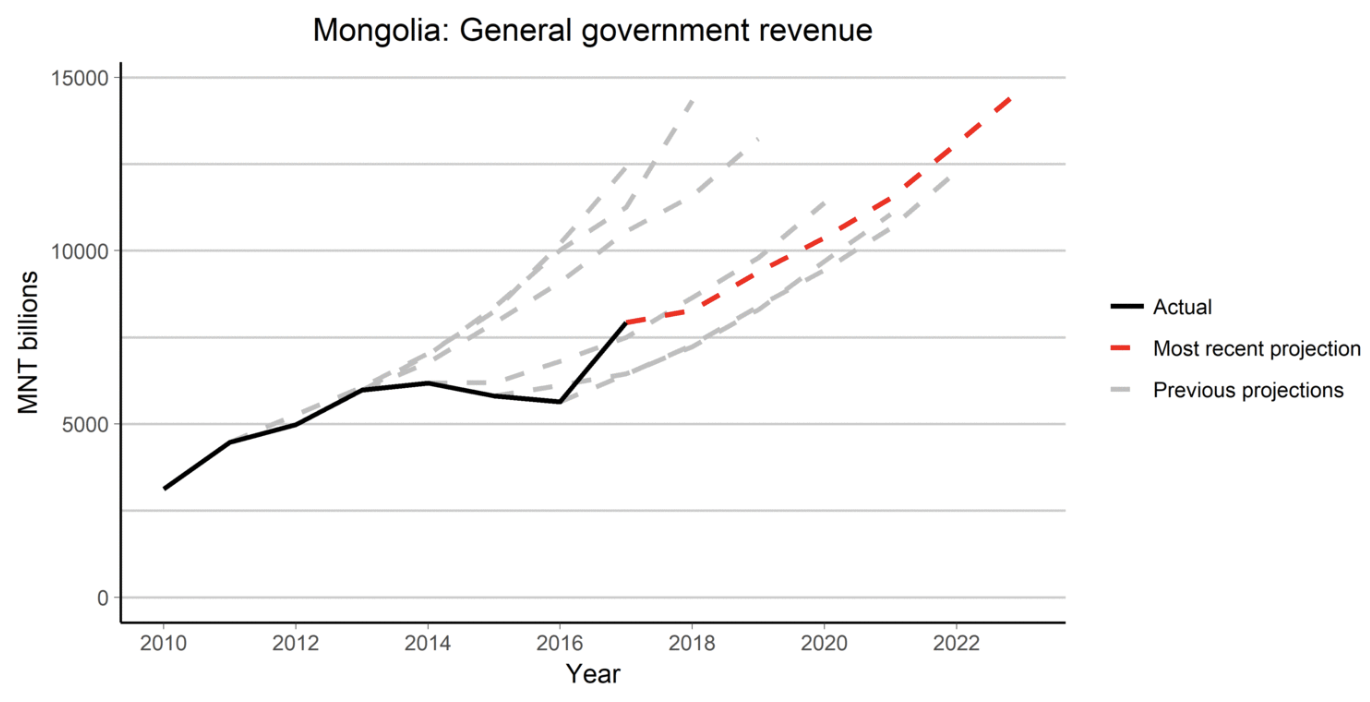

A second use case is to revisit how previously anticipated natural resource booms played out. As we showed in “Evidence for a Presource Curse?,” major natural resource discoveries can lead to elevated economic expectations (as illustrated by IMF gross domestic product growth forecasts), but subsequent economic performance often falls short of rosy forecasts. One example of this phenomenon is Mozambique, where IMF forecasts suggested that per capita GDP was going to double in just a few years as a result of gigantic gas discoveries. But the investment needed to develop these gas field has been delayed repeatedly. Another case is Mongolia, which experienced an influx of investment around 2011, but the expected boom in coal and copper revenues did not materialize. The IMF was not the only actor who proved to be overly optimistic: national governments, investors and lenders all contributed to increasingly enthusiastic expectations in both cases. Now the governments of both Mozambique and Mongolia are facing debt crises, having borrowed heavily in anticipation of the boom.

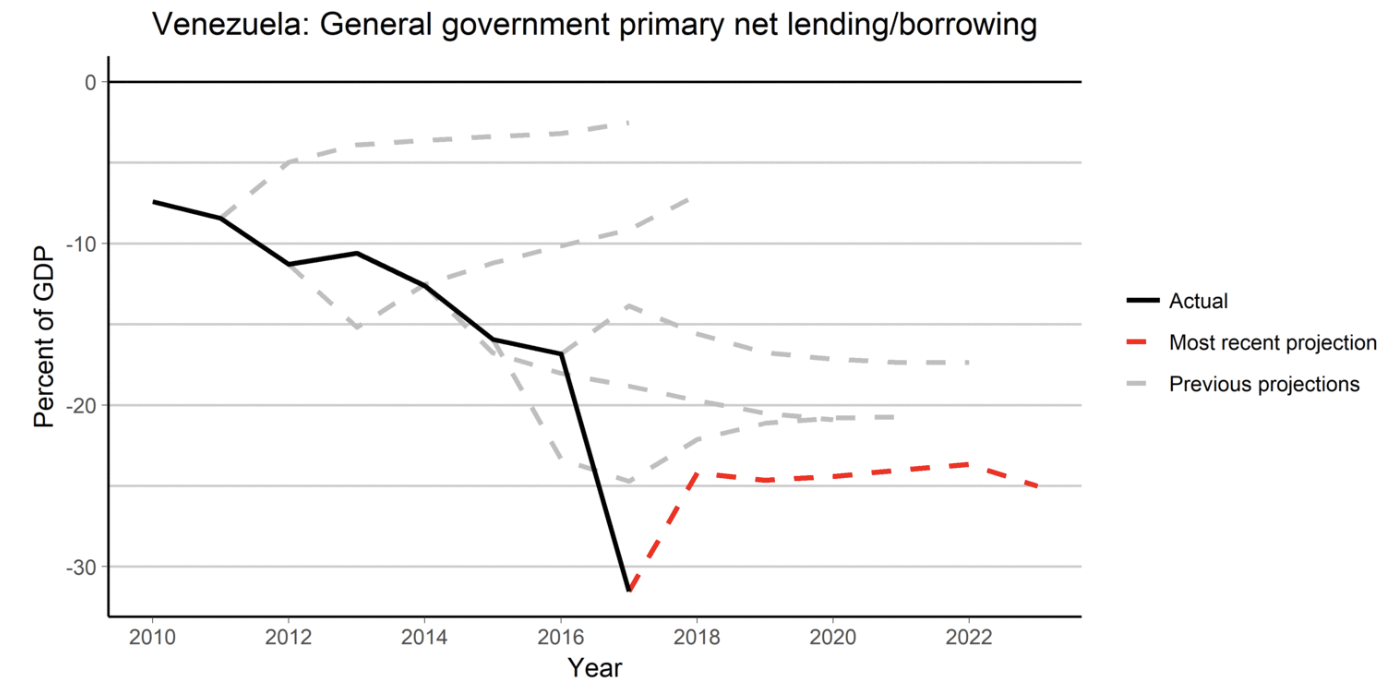

One could also look into how countries that depend critically on oil exports have responded to a prolonged period of low prices (even as they currently rebound), exploring the trajectory of government deficit (or alternatively the current account or economic growth). Venezuela and the United Arab Emirates both were dramatically hit by the oil price shock. But while Venezuela’s budget deficit widened beyond what was forecasted, the UAE’s budget balance improved quicker than forecasted by the IMF following the oil price crash.

Venezuela and United Arab Emirates budget balance

These are just a few illustrative examples of how IMF projections might be used to better understand shocks, uncertainty and volatility linked to natural resources. Others have compared the forecasted and actual impacts of austerity policies in Europe, the build-up of new debt after debt relief in Africa or the track record of the IMF at forecasting recessions. We hope that our new tool, which is available under an open license for reuse and adaptation, will encourage others to use the IMF data in innovative ways.

David Mihalyi is an economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Tommy Morrison is a research and data associate at NRGI.